How the pandemic is affecting funding for nutrition

3 trends that will shape the outcome of the Nutrition for Growth Summit

2020 was meant to be the year for nutrition, with global and country partners working toward the Nutrition for Growth Summit in Tokyo. Now, the COVID-19 pandemic threatens to worsen the state of malnutrition and has caused economic hardships across the world that present new challenges to the nutrition community. While the Government of Japan assesses the best path forward for the timing of N4G, the nutrition community must get ready for a post-pandemic Summit by recognizing and preparing for changes to key parameters of resource mobilization for nutrition.

Three key issues will be important drivers for nutrition financing: the worsening state of malnutrition, challenges to resource mobilization, and the daunting trend in nutrition-specific aid based on new data from 2018.

1. COVID-19 could deepen food insecurity and malnutrition, and, as a result, magnify the financing need.

The World Food Program has warned that the number of people facing food insecurity could double from 135 million in 2019 to 265 million in 2020 — due to the economic impacts of COVID-19. The prevalence for wasting also will likely increase as people face higher risks of acute food insecurity. A recent Lancet article estimates that if the coverage of essential maternal and child health interventions decrease and the prevalence of wasting increases, the number of children under 5 dying each month could increase by 10–45% (under different scenarios of severity; 42,000–193,000 of additional child deaths per month), where the increase in wasting prevalence would comprise about 18–23% of these additional deaths.

While results are still forthcoming, significant efforts are underway to better estimate the impact that COVID-19 will have on health and food systems and to advise on required responses.

2. The coronavirus has shocked the global economy, raising concerns for social sector funding.

The IMF suggests that the world economy may experience a global recession worse than the 2007-09 global financial crisis, where global growth in 2020 is projected to fall to -3%.

For country governments, the forecasted economic slowdown in LMICs, paired with increasing domestic health financing needs for COVID-19 response efforts, all point toward lower fiscal capacity to allocate resources to nutrition. Sub-Saharan Africa has been significantly impacted by COVID-19 with economic growth forecasted to fall sharply in 2020 — leading to the first recession within the region in over 25 years. At the same time, the COVID-19 crisis has increased domestic health financing requirements for countries as a result of increased pressure on their health systems. To cover the additional cost of these response efforts, there are risks of decreases in funding among nutrition-relevant sectors such as education to make room for emergency spending on COVID-19.

For donors, while we cannot say for sure how aid will be affected, development aid is unlikely to see major increases — and might even decrease — due to economic hardships faced by donor countries along with the urgent need for emergency support taking precedence in the short-term to respond to capacity constraints. However, we are already seeing significant commitments to COVID-19 response efforts, including a $160 billion pledge from the World Bank over 15 months in response to health, social and economic impacts of the pandemic; this includes $50 billion of IDA resources on grant or highly concessional terms. And bilateral donors, including the U.S. government, have provided more than $900 million in emergency assistance.

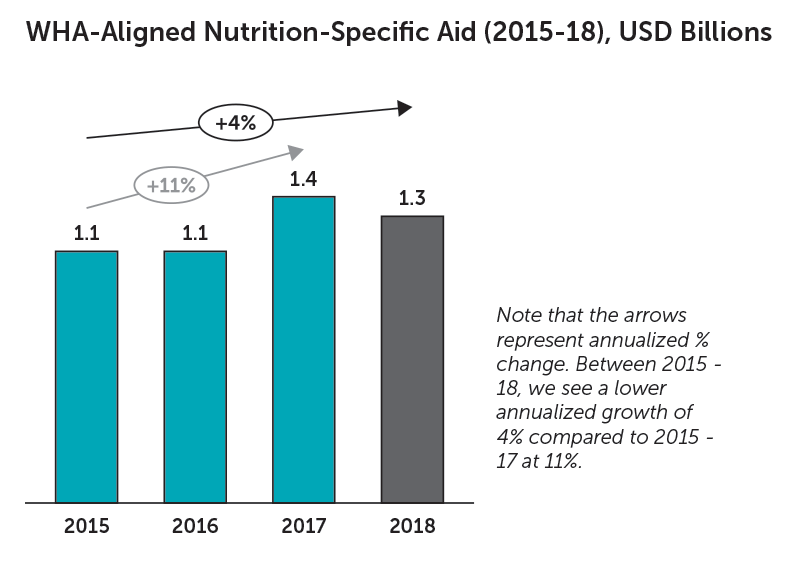

3. The global trend in donor aid for the WHA nutrition targets is not as positive as previously thought.

R4D has been tracking nutrition-specific aid to the WHA targets for stunting, wasting, anemia and exclusive breastfeeding since 2015 and found that aid supporting the targets increased between 2015 to 2017. However, new 2018 data suggests a less positive outlook. We ran a high-level analysis of 2018 disbursements using assumptions derived from our in-depth 2015-17 analysis and found a decrease in nutrition-specific aid in 2018 (a 7% or $100 million drop), which results in a flatter multi-year trend. This is in part driven by a decline in disbursements coded under the Basic Nutrition purpose code, which also experienced an 11% decrease in 2018. While our 2018 estimate is based on a more limited analysis of newly available CRS data, the drop in Basic Nutrition disbursements is consistent with our 2018 estimate. Given this trend, any potential slowdown in development aid mentioned above raises even more cause for concern for nutrition programming.

While we cannot say for sure how COVID-19 will affect future nutrition financing, our positive momentum toward the nutrition WHA targets is clearly at risk. The nutrition community will need to push more than ever to mobilize funding commitments at the N4G Summit in 2021, and, in the meantime, make sure that recovery efforts for COVID-19 are as nutrition-sensitive as possible.

Photo © Dave Cooper/USAID